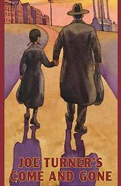

The Second Coming (on Broadway) of August Wilson's Joe Turner

Pittsburgh Beginnings

August Wilson’s early life reads like a Dickens novel, if Dickens had been writing about African-Americans in the 1950s. Born on August 27, 1945, Frederick August Kittel and his five siblings were raised by their African-American mother, Daisy Wilson, after their Caucasian father, a German baker also named Frederick, disappeared from the family’s life. Daisy and her kids lived in a two-bedroom cold-water flat in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, which Wilson later made famous as the setting of his plays.

Little “Freddy” was taught to read by his mother at age four and remembered wearing out the library card he got at five. He later told a Pittsburgh interviewer that his mom “had a very hard time feeding us all. But I had a wonderful childhood. As a family we did things together. We sat down and had dinner a certain time…we listened to the radio.”

Away from home, things weren’t so rosy. His mother remarried and the family moved to a white neighborhood, where Wilson became the only black student in the freshman class at a Catholic high school. “There was a note on my desk every single day,” he later told The New Yorker. “It said, ‘Go home, nigger.’” He transferred first to a vocational high school, which wasn’t challenging enough, then was forced to re-enter ninth grade at a public school near his home. When the budding young writer presented his English teacher with a 20-page paper on Napoleon, she accused him of plagiarism. In response, he secretly dropped out of school and began spending weekdays reading at the Carnegie Library—which eventually awarded him a high school diploma to go with his two dozen honorary doctorates.

In addition to his self-imposed education, Wilson who took his mother’s last name at age 20 immersed himself in the street life of his old neighborhood in the Hill District, sitting quietly and listening to the men who congregated at a cigar store called Pat’s Place. “I just loved to hang around those old guys—you got philosophy about life, what a man is, what his duties, his responsibilities are,” he said in a 1999 interview in The Paris Review. “That’s where I learned how black people talk.”

Supporting himself with odd jobs, Wilson scribbled poetry on napkins while hanging out in diners in his free time. “The exact day I became a poet was April 1, 1965,” he remembered, “the day I bought my first typewriter,” purchased with $20 his older sister gave him for writing a term paper. At 23, spurred by his interest in the Black Power movement, he decided to try another medium, co-founding the Black Horizons Theater “with the idea of using the theater to politicize the community or, as we said in those days, to raise the consciousness of the people.”

Blossoming of a Playwright

In an era that celebrates instant success, it’s worth noting that August Wilson made his first stab at playwriting at age 28 and didn’t make it to Broadway until he was 39. His first few years with Black Horizons were spent mostly as a director, a craft he taught himself by reading a book called The Fundamentals of Play Directing. “And I acted when the actors didn’t show up,” he told The Paris Review. “I knew the lines and I took over more times than I wanted to.”

Wilson’s earliest plays were written in a faux-artistic style very different from the dramas that made him famous. “I didn’t recognize the poetry in the everyday language of black America,” he confessed to The Paris Review. Over time, he cited “what I call my four Bs” as influences: the blues particularly Bessie Smith, the short stories of Jorge Luis Borges, the politically charged plays of Amiri Baraka and the collage art of Romare Bearden, as well as the overall philosophy of James Baldwin, who challenged other artists to articulate the black tradition. “I thought, Let me answer that call,” Wilson said.

After he moved to St. Paul in 1978, Wilson’s playwriting career picked up steam. He took a job at the local Science Museum adapting Native American folk tales into children’s plays and began work on what would become his Century Cycle. Jitney, set at a Pittsburgh gypsy cab company in the 1970s, was submitted and rejected twice by the Eugene O’Neill Playwrights Conference in Connecticut. But program director Lloyd Richards gave a thumbs-up to Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, about the struggles of 1920s blues musicians in Chicago. Richards guided the play to Broadway in 1984, beginning a collaboration that would extend to six plays, a Tony Award and a Pulitzer Prize.

By the time four Wilson plays had debuted on Broadway, the playwright realized that he had set each one in a different decade. He then decided to challenge himself to write a total of 10 plays that would illuminate the black experience in America in the 20th century “by putting that culture onstage,” he said, “and also to demonstrate that there is no idea that cannot be contained by black life or black culture.”

10 Decades, 10 Plays

The complete Century Cycle consists of Gem of the Ocean 1900s, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone 1910s, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom 1920s, The Piano Lesson 1930s, Seven Guitars 1940s, Fences 1950s, Two Trains Running 1960s, Jitney 1970s, King Hedley II 1980s and Radio Golf 1990s. All but Jitney received Broadway productions.

The plays were not written in chronological order, but Wilson managed to suggest a throughline of characters who appear at various ages, particularly the mystical Aunt Ester, who is supposedly almost 300 years old at the time of Gem of the Ocean. “His characters were filled with humanity,” Constanza Romero, Wilson’s widow and literary executor, told Broadway.com in a recent interview. “None of the characters is perfect, but every single one has a vision and an inner strength. No one is defeated.”

Self-taught as a playwright, Wilson successfully walked the tightrope of presenting realistic stories while occasionally weaving in otherworldly elements. “For all the magic in his plays, he was writing in the grand tradition of Eugene O’Neill and Arthur Miller, the politically engaged, direct, social realist drama,” playwright Tony Kushner explained. “He reasserted the power of drama to describe large social forces, to explore the meaning of an entire people’s experience in American history.”

“The goal [of completing the Century Cycle] was fantastic,” says Romero, the mother of Wilson’s younger daughter, Azula Carmen, born in 1997 in their adopted home city of Seattle. The playwright also had an older daughter, Sakina Ansari, to whom he dedicated Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. “I saw him start on a new play before the previous one opened. By the time Seven Guitars was produced, he had already started King Hedley II. The [idea of the] cycle kept him going; it was the fuel.” Wilson finished the tenth and final play, Radio Golf, just before his death from cancer on October 2, 2005, at the tragically young age of 60.

Return of a Classic

In its first Broadway incarnation in the spring of 1988, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone opened in the shadow of Fences, which was still running a year after winning the Best Play Tony. New York Times critic Frank Rich’s rave review declared that Joe Turner “gives haunting voice to the souls of the American dispossessed,” exploring the aftermath of slavery as experienced by the men and women who take up residence in a Pittsburgh boarding house in 1911.

“Foreigners in a strange land, they carry as part and parcel of their baggage a long line of separation and dispersement,” Wilson wrote of the characters in his introduction to the play. His inspirations included artist Romare Bearden’s painting “Mill Hand’s Lunch Bucket” and a W.C. Handy blues song about Joe Turner, a plantation owner who supposedly kidnapped and enslaved blacks after the Civil War.

The arrival at the boarding house of Herald Loomis and his 11-year-old daughter drives the action of Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. The mysterious and menacing Herald claims he spent seven years in servitude to Joe Turner in Tennessee before heading north in search of his wife. The Loomises join a group of richly drawn characters such as Bynum, an old man with psychic powers; a young rogue named Jeremy; and Mattie and Molly, two girls looking for love. Anchoring the play are the hard-working couple who own the boarding house, Seth and Bertha Holly.

“It was one of his favorite plays,” Romero says now, “because he was in a completely different place [as a writer] after he finished it. He always said that after he wrote Loomis’ speech about bones walking on water, rising above the water and coming to life, he felt he didn’t have to write another line.” In spite of the play’s arresting images and lively characters, the initial Broadway production of Joe Turner ran for only 105 performances. It earned Tony nominations for Wilson, director Lloyd Richards and four actors, with L. Scott Caldwell winning the featured actress prize for her performance as Bertha.

Two decades later, Bartlett Sher, who brought new life to Clifford Odets’ Awake and Sing! three seasons ago before winning a Tony for South Pacific, is directing a new Broadway production of Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, set to open on April 16 at the Belasco Theatre. As artistic director of Seattle’s Intiman Theater, Sher had met Wilson, but they didn’t know each other well.

“When Bart called me, he was passionate about the play and respectful about its place in history,” Romero says of Sher, one of the few Caucasian directors to mount major Wilson productions. “Bart’s understanding of the poetry of theater was a good fit because this play is one of the most poetic. There are a lot of complex stories being told, and the ending borders on abstract. Each person who sees it can experience the play in different ways and on different levels.”

Sher’s revival for Lincoln Center Theater “will be produced in a way that not many people have seen August Wilson produced,” Romero previews, “in an open, painterly style inspired by Romare Bearden.” This “tapping in to the poetry of the play” is in keeping with the man Romero fondly remembers as “a person who lived his life in a very intense, ‘ratcheted up’ way. He used that intensity to arrive at a very poetic way of expressing himself and the way he saw his world.”

Asked if she sees her late husband in any of his characters, Romero exclaims, “All of them! I hear his voice in Seth, who pays attention to every detail and takes everything personally. His warmth is like Bertha, and the sense of higher searching is like Loomis. He was so warm, such a real human being. His humanity and his interest in the world live on in his plays.”